They don’t make them like Gene Gutowski anymore. He had it, baby—and whatever it is—he still has it in spades. (GG died at age 90 in 2016).

That’s the bottom line.

Call it style.

Call it elegance.

Call it class, dahling.

The cat is way cool.

I’ve got personal history with Mr. Gutowski. We first met at a little party in Zoliborz in 1992. I’d been invited to his house because I’d written a profile for The Independent about Gene’s production of Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden at Teatr Studio in Warsaw. He liked the piece. I was a roving reporter with fledgling filmmaking ambitions. And there I was in the home of a guru, the man who single-handedly produced Polanski’s first three English language films Repulsion, Cul de Sac, the Fearless Vampire Killers. I knew them well from college film courses. The hostess was a knockout. His fourth wife, Dorota, was 30+ years younger than Gene, a lithe ex-model with sensuous limbs and a magazine-cover face.

Gene was in his mid-sixties then, but in his heart he was, as always, ageless.

But that was then, and this is now. For the last six weeks, Gene and I have been dancing. My first email requesting an interview/profile met with a genial and heartfelt, “Nice hearing from you and thanks for asking but not as I no longer give interviews.”

Gene was enjoying a winter in St. Martins at a fine hotel on Orient Beach and well who could blame him for wanting to be left in peace, already? However, being the ever intrepid reporter, often deaf to the word, ‘No,” I thought I’d give it the old college try once more. We were dancing a slow Mazurka, a kujawiak in 3/4 time. I needed to up the tempo. An oberek was called for.

I’ve done my share of ass-kissing in show business, so I did what any self-respecting scribbler would do. I waited a week and then wrote the most flattering response I could muster. I got back an elegant (or course!) reply asking if Gene could email me a copy of his book, From Holocaust to Hollywood, which would be easy to read since he wrote it in English. My Polish skills are not what they should be.

Gene continued, “If (the conditional conjunction, baby) we do it, could the story center on the importance of elegance at all times? At 85 I have survived much and occasionally succeeded in life by being elegant.” He suggested we do the interview in St. Martin

“Let me think about it,” I wrote back.

Just kidding. I called the boss and told him we were “in.” A little Vaseline goes a long way, as Gene would say.

My editor said, “Let me think about it.”

Soon the plot hatched. Both Andrej and I would fly to St Martin. We informed Gene of our plans and booked the trip. Ready to rock and roll. Then on Good Friday, Gene emailed that he had to return to Poland immediately. He’d run out of his special heart medicine, and we’d have to do the interview in Warsaw. What the hell, I thought. Who needs an express trip to a Caribbean paradise just on the cusp of spring, right?

Gene returned to Warsaw on a Thursday and we were to meet the following Monday. Monday morning came and I called. “I’m sorry, my dear. But I just don’t feel up to meeting yet. I’ve got doctors to see, and we are getting ready to move flats . . . I’m busy on Wednesday with an interview for a French documentary about Roman. “How about Thursday?”

Well, why not? This is the week of the Smolensk catastrophe (much of the Polish government including the former President killed in a plane crash in Russia on the way to a Katyn memorial meeting) so the atmosphere is dolorous and tense throughout the city, one of those teeth-clenching time warps soaked in weirdness—exactly the opposite of what you want when you are trying to land a Big Fish and Gene is a Marlin.

Make no mistake about that.

He knows how to run with the line into the deep water, if you let him. On top of that Roman Polanski’s troubles continue. That’s got to hurt. Polanski wrote the epigraphs for Gene’s autobiography saying, “Gene is one of the most important characters in my life. Ever since I met him 40 years ago he seems to be present at the most pivotal moments of my existence. I value both his friendship and his professional advice. I’m deeply indebted to him for launching me in my international career, but I do admit that I feel a pang of jealousy that he seems to have managed the first half of his life without me.”

(I hadn’t seen Gene for several years. I’d been spending a lot of time in the States and in Central America, where one fine day in Nicaragua I ran into a spry 83 year-old New Yorker called Ed Brown Jr. who just happened to be Gene’s long lost “cousin” from the early days in New York in the fifties. That was two years ago. I put Ed in touch with Gene and they renewed their acquaintance.)

Now as I rounded the corner into Plac Trzech Krzyzy on a bright April day, I wondered if he still had that certain je ne sais quoi, that spark, that knowing twinkle in his eye. I wondered how hard a time he was going to give me. I wondered if he was going to offer me a drink. If he did I knew everything would be okay. I’m used to charming old rogues and their shifty ways. It’s like water off a duck’s back. That’s what I tell myself anyway.

The flat he is leaving is a simple one-bedroom, located perfectly in the center of Warsaw. He lives there surrounded by a few prized possessions and objects d’art with his companion of the last decade, the svelte and comely, Joanna, a former documentary filmmaker he met while making The Pianist.

The door was standing open as I exited the lift on the fifth floor, and Gene was waiting inside seated on a sofa, Heffner-like in a bathrobe with his nickname “Gucio,” embroidered on the back—a gift from one of his sons.

“Just push the door closed,” he says.

He welcomes me with that sonorous burr, smooth as a cat’s purring and guaranteed to charm.

“Hello, how are yaaaa,” he drawls—the last word accentuated British-style, but the overall voice relaxed, cool and mid-Atlantic.

“Dr. Gutowski, I presume,” I said, feeling like the reporter Stanley finally encountering Livingston in Africa . Warsaw is a jungle after all.

“I brought you a bottle of red,” I said.

“You didn’t have to do that, but thank you very much.”

“Least I could do. By the way, I enjoyed your book. Gene.”

“Too much sex. Don’t you think?”

“Didn’t bother me.”

“I thought it was too much,” he says.

“Why’d you put so much sex in it then?”

“To sell it better. But I overdid it, and that can ruin the effect. On the other hand I have a wide audience of younger people (smiles). It’s a different holocaust story. They couldn’t catch me because I was busy fucking somewhere. “Holofuck” is more like it.” A throw-away line. You don’t hear a lot of Holocaust puns.

Now we are seated around a large Igor Mitoraj sculptured coffee table. Gene lights a thin cigarette, sits back and asks with a captive smile, “I see you have your Starbucks coffee. Very American. Now what have you been up to since I last saw you?”

Typical Gene. Always curious about other people. So I give him a brief rundown and then he leans forward and sighs, “Now what the fuck do you want from me?”

What indeed? It’s hard to be finite on an infinite subject, especially when the subject is an expert story teller who has done things that most men would give their left nut to have, if not done, as least witnessed. For example, do you want to talk about women that Malemen would love? The mind reels. He produced the film that made Catherine Deneuve an international star (Repulsion). He gave Jacqueline Bisset her first screen test (Cul de Sac). He was once pictured in the French tabloids with Brigitte Bardot at the door to her Paris flat (he was subbing for Warren Beatty who’d instinctively ducked around the corner to avoid paparazzi hiding in the bushes). He produced the film during which the most star-crossed of famous couples, Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski, became lovers (The Fearless Vampire Killers). He was an habitué of The Playboy Club Casino in London in the late sixties when that was the most hell-raising club in the world with regular guests including the Beatles and the Stones and an A-list of film celebrities from both sides of the Atlantic.

Take a breath.

“Let’s start with the importance of being elegant, why not?”

Gene lifts his glass, “just a little beer,” to wet his whistle.

“Look,” he starts in slowly and deliberately, “I came from an elegant family and grew up used to the finer things of life. Eugene was not my real name. It was Witold, which I had to change during the War . . .”

Gene! Perfect! His assumed name, Eugene, means “well born,” and suggests something inherited, something in the genes, as it were. He was born Witold Bardach into a secular Jewish family—his immediate family vanished in the Holocaust—and into a Poland that no longer exists. The town, Rawa Ruska near Lvov, became part of Ukraine in 1945.

“So I’m coming out of Europe the sole survivor of a famous family. Everybody got killed off. You lose family but you don’t lose your sense of entitlement. You come to accept certain standards of conduct. . .”

Loss. A week of loss. A life of loss. An old Polish story. Gene retreats from the sitting room to his office and returns slowly—he walks, but not so well any more—clutching a heavy album full of photos. A telling fact: In his memoirs the first twenty-two years of his life take up half the book, which ends with the making of The Pianist. His sharp focus on his youth (especially considering its circumstances) is not unusual amongst men who have done great things, witnessed great events.

“I can show you photographs that I came from very elegant cultured people. Even living in a small town near Lvov my mother read a French newspaper every day. My father spoke five languages and because of his linguistic abilities he was a liaison to English and French officers during the Bolshevik War.”

Indeed it was Gene’s knowledge of languages, including fluent German and English that saved him during the war, not to mention, a certain savoir faire, which included always being well-groomed and well-dressed.

Gene’s always had a genius for survival and re-inventing himself.

“Who was going to kill an elegant young man who spoke fluent German? Are you crazy?” he says.

Now he points out his beloved uncle Andrew who like his father was a role model “a very sophisticated man,” who was shipped out to a Gulag from Lvov . Later he joined Anders army in Persia and was in all the campaigns in Africa and Italy .

Gene says, “Now he was an elegant man, and his wife came from an elegant family and after the war they immigrated to Brazil . Of course I thought he was dead too. Then after the war I was talking to someone in New York and mentioned I’d lost my uncle Andrew in the war. He said what are you talking about? You didn’t lose him. I just saw him boarding a ship for Brazil . He’d been employed as the head of a Firestone factory for some years in Sao Paulo .”

Gene brought Uncle Andrew over to London in the eighties and bought him an apartment right next to his. “It gave him another five years of good life. He died in 1990. He was then 87. He was a very, very cultured, sophisticated man.”

The caption under Uncle Andrew’s photographs from the 1930s reads, “Always Elegant and Handsome.”

Is there a specific instance where being elegant saved his neck?

Gene says, “Well, even before I needed my neck saved, when I was 15 or 16, I fancied myself as a great lover and a great seducer. I remember using three different colognes, including one for my hands to touch their lovely faces. You know, I was crazy.”

He points to another picture and says, “My uncle Bronislaw, the dentist, was insanely elegant. He had his suits made in England . Remember there was no ready-to-wear back then. He drove a large Packard with two windshields and enormous headlights. I don’t know where he even got that from.”

And then softly he adds, “He was a bit of a prick actually.”

“All right, now here’s a photo of my Uncle. Look at him! Bronislaw’s wife drove a Bugatti, and he drove that Packard . . . Here, he is wearing patent leather shoes with his uniform. I mean who does that? Crazy! Still it shows you a bit of style in a regimental photo from the 1921 war.”

So his background was the key to his survival?

“Absolutely,” Gene says without a shadow of a doubt. “I call it a sense of entitlement. That is who I am and this is what I respect. Let’s face it. I had a problem. My entire family was killed off in 1942 . . . for being Jewish. They just couldn’t save themselves. Sometimes I’ve held it against my poor father that he thought of trying to save his parents before saving himself and his children. Anyway, I came to Warsaw but with the knowledge that I had to be elegant within the means I had. Sometimes I was hungry. I don’t remember a single time during the whole occupation that I didn’t shave because once you stop shaving, I thought, you let yourself go. And razor blades were not easy to get. You used to sharpen them inside a glass.”

Elegance of mind and good tailoring were survival tools. Grace, good humor and youthful daring were an invisible cloak worn against the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Good form was a way to beat the devil at this own game. But was he courageous?

“Courageous? I don’t know. I was totally foolish. I’m not a physically courageous man. I’m not the type to jump into a river to save someone. I want to say also that people have different standards. They do different things under pressure. . . informing or collaborating with the Germans. None of that for me. . . Sometimes you hide under the lantern. Sometimes it’s best to hide where there’s the most light.”

Famously, he smuggled Luftwaffe radios to the AK while working in the Junker factory in Warsaw. Was that the scariest time of his life?

Gene pauses and chuckles. He lights another thin cigarette. “The scariest moment? Believe it or not an American officer scared the shit out of me. It was Germany after the war. I was stationed in Starnberg, and I was courting this American lady, Zillah Rhoads from Culpeper, Virginia . We used to travel all over the place sightseeing on the weekend. Being in the CIC (US Counter Intelligence Corps) I could go where I wished. So we went to visit some of those palaces near Munich built by that crazy King Ludwig. We were on a boat on the lake. I always had to carry a pistol which this time I’d put in my briefcase. When I had to pay for the trip I opened the briefcase, and the German conductor of that little boat saw the pistol. So he got immediately got on the phone and called the American Military police saying ‘You better get over here, there’s a man with a gun.’ So at that point we are getting into my elegant convertible slowly, slowly and suddenly a jeep rolls up with a young lieutenant MP who approaches, obviously scared shitless. He has a big .45 pointed right at my nose and his hand is shaking. Well you don’t want to be hit by a .45. I put my hands up. He says “Where’s your gun?” and I explained carefully who I was and why I could carry the gun. And that was my scariest moment of the war because he had a cocked and loaded gun pointed at me.”

So you were almost killed by the people you were working for? Is that a metaphor for life?

“Well you never know,” says Gene. “The MP was young and nervous and he could have gotten off by saying he had to kill me in the line of duty and so forth.”

The moral of that story is the key to success in life.

“Don’t be afraid. . . Or, at least, don’t show it,” says Gene. “Make the most of your situation whatever it is and do it with class. For example, there we were at the end of the war when Germany was destroyed and poor. Zillah and I wanted to arrange our wedding at St Lukas cathedral in Munich . It was an evening wedding and I had to organize the whole thing. Black market coal to heat the church. A wedding cake from the army PX in Garmisch—a beautiful three-tier cake. I drove from Garmisch in a jeep with one hard on the wheel and one on the cake. I needed formal wear for the evening event but had no tails so I borrowed them from a rather portly doctor I knew in Garmisch. Unfortunately I had to have them taken in. Poor fellow. I never told him what happened, so when he got them back he must’ve thought he’d put on a lot of weight. Always elegant and handsome.

Familiarity with danger may make a brave man braver, but it usually makes them less daring. Not so in Gene’s case, though he would deny it if I said it to his face.

Here’s a case in point. We’ve all heard of clothes to die for. It’s a saying. But what about clothes to kill for? We are not talking about browsing through the duty-free at Schiphol or shopping for Armani in Milan .

“Do you know how I got my first suit after the war? Through thick and thin throughout the war I had kept this suit that I had tailored in Warsaw. That was so that at the end of the war I’d put on the suit and be elegant.”

Of course. You’d do the same wouldn’t you, dear reader?

So imagine. It’s Spring 1945. Everyone’s dashing through Austria to the German border chased by the Russians. All Gene has is his tattered “Todt” uniform (he’d been forced into working for the Nazi civil and military engineering corps). After days of walking amidst refugees of all stripes, he’d stowed his rucksack on a wagon, so he didn’t have to carry it.

Then here come the Russian tanks to cut off the group before they made it to the American sector. Gene legs it fast as he can.

“I was in pretty good shape then, 19 years old—not like now.”

He makes it to the bridge, crosses over the Ems River into the hands of the Americans. But he’d left the suit on the wagon! That wouldn’t do. His Todt uniform would make him a marked man. The Americans were still trying to gather up uniformed people and put them in POW camps.

Gene had to ditch the uniform and get some proper clothes in a hurry.

What to do in such a sartorial crisis?

The Gutowski solution: “I wandered into this little town nearby and kept looking till I saw a sign for a tailor, Schneider. I went in and basically committed armed robbery to get the poor guy to provide a suit. Fortunately he had some suits on the rack that hadn’t been collected. I selected a dark blue one. He made a few alterations and once he realized I wasn’t going to shoot him, his wife brought out some tea and cakes which we proceeded to enjoy while I browsed around and picked out some shirts, a tie and some shoes.

Talk about cornering the market in chutzpah. His language skills and his suit, according to Gene, impressed the American officers so much that pretty soon he was interrogating Germans for the US Counter-Intelligence Corps and having his suits made in Munich.

“You know, I found a glove-maker in Munich and eventually had 19 pairs of gloves made. That was me,” he says with a shrug as he points to a photo of himself in uniform in Paris . He is standing on a virtually deserted Champs Elysees of an afternoon wearing a glove on his left hand and clutching the other in his right.

Gene says, “You either have style or you don’t. What can I tell you?”

“So whether you have a million bucks or not you say this is me and I’m somebody. Is that it?” I ask.

“The important thing is to look like a million bucks,” says Gene. “All right, that’s enough for today. I’m a little tired.”

He’s right. It wouldn’t be polite to intrude any longer. Besides he’s eighty-fucking-five. This is an magazine story, not an assassination attempt. That said . . . I still didn’t get my drink.

* * *

After another necessary postponement—this is Gene Gutowski after all—we finally meet again a few days later. Gene and Joanna are packing. The Smolensk funerals are over. The atmosphere is brighter. Gene seems more rested. The jet-lag has faded. Things are looking up. I have brought another bottle of wine and twenty yellow tulips for Joanna.

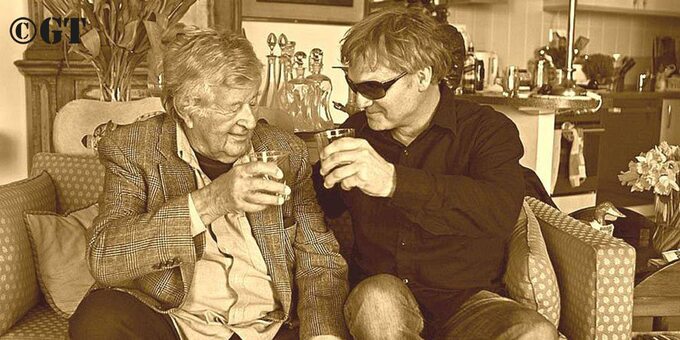

After we are seated on separate sofas around the Mitoraj table, Gene says, “Would you like a drink?”

“Absolutely,” I say.

“How about a little whisky.”

Joanna producers some Johnnie Walker Black and kindly pours us a couple of splashes.

“No rocks,” she says.

So Gene and I sip it neat.

I start off by asking Gene advice about whether or not I should buy a nice Italian suit I’ve spotted, exactly my size, 42L, in a second hand shop in my neighborhood. The only problem is that it’s kind of well . . . brown leaning to rust color. I usually favor solid black or dark grey pinstripe.

“You can carry that off. With my coloring I couldn’t,” says Gene.

Most of the really good clothes I have ever had were bought in London, but that’s been a while. Style has changed, perhaps even disintegrated, the elegant and the chic blended with kitsch. Casual style is more a personal revelation than a coded uniform suggesting status. Billionaires dress down, but princes still dress up.

Gene jumps on the subject. “Generally my generation dressed to look older like our fathers,” says Gene. “Now old men try to dress like their kids. In the fifties whatever elegance there was in the US, it was on the eastern seaboard with Brooks Brothers (which Gene favors nowadays). Tripler and Paul Stuart lead the way with Dunhill for Blazers, Lock for hats, which we all wore, and Lobb for shoes, though I always preferred the light Italian Testoni of which I’ve had a fine pair for over 30 years. England was of course a paradise for men’s clothing since the days of the Regency dandies and London is still a Mecca for all the things a well-appointed man could wish for from Saville Row tailors to shirt makers on Jermyn Street like Harvey Hudson or Turnbull and Asser with Daks for trousers and Holland and Holland for the hunting and sporting man. There are countless places for canes, umbrellas, colognes, hairdressing etc. etc. Until recently there were few places for ladies to shop. . . On the whole, we, Americans (Gene is a citizen of both the US and Poland ) have problems with elegance mostly because of our bulk. As they say, you can never be too rich or too thin. I remember in my days in the Virgin Islands in the ‘80s, a suave Italian called Flavio Briatore, later the owner of a Formula One team, tried to open and run a branch of Regine’s night club and failed miserably. While the locals, many of them black of course, would dress up splendidly with good trousers and a shirt, the Americans seemed to insist that it was their birthright to show up at night in sweaty t-shirts exposing hairy backs with dirty shorts and sandals. In Florida old men run around in shorts and Nike shoes, and California? Forget it. Only the British upper class had the right attitude to being casually elegant. I remember once being invited to a formal pheasant shoot, I had to wear a tie and beat the hell out of my tweed suit for it to look properly old and worn out. . . Italy of course had great tailors with Caracene and Schifonelli and Angelo’s all together leading the way on the Via Condotti in Rome. Gucci, too. Today there is obviously Armani and Zegna but for mass consumption. . . It’s a pity that Polish society doesn’t have this elegance of spirit which translates into the other stuff anymore. Because by acts of omission and commission the whole middle class was eliminated, the landed gentry gone, the Jews gone. This whole society now has peasant roots. They come from small villages and towns. . . In 1940 there were 80,000 people with higher education in Poland and they killed 22,000 of them in Katyn!”

Doesn’t this lack of grace, if you will, translate to contemporary culture as a whole, including films?

“Listen, I don’t give a fuck about contemporary culture,” Gene says with a pleasant laugh.

Gene was always a big picture guy. No pun intended.

“You asked me a question. Here’s the short answer. My father said it takes 24 years not eight to make a gentleman. Three generations of gymnasium. Who taught people how to dress and how to eat during the war and under communism? Still, Poland has made a giant step forward in the last twenty years. You could even see it in connection with the recent catastrophe. I was amazed at the number of men in dark well-cut suits. The Prime Minister is obviously a Zegna man.”

Gene’s priorities bring to mind something Miles Davis once said, “For me music and life is all about style.”

For Gene, the swinging sixties in London were his finest hour. Filmmaking and life were all about style—maybe even style as fetish.

“I like the British and did well in London. What a time! Plenty of style. Doug Heyward was the tailor to celebs. He started very small working with a Ukrainian called Dimitri, who had a tailoring outfit in Fulham. Doug was the front man who came to your house and did the measurements. He opened a place in Mount Street later. I remember when Roman came to London in 1963 and tore up his only pair of trousers. Dougie did the repairs for him. You go into his shop and gossip and meet friends. Everyone had suits made by Heyward. I even had a suit made for Uncle Andrew and his suits were very special because they required 20 pockets. He carried absolutely everything with him that he thought he might need.”

Gene might be termed one of the Princes of London during the swinging sixties. He was as hip as you could get. He went to London to make a Sherlock Holmes series for TV and ended up staying. The series didn’t come off, yet he made a fun but forgettable film called Station Six Sahara starring Carol Baker (a siren of the time) and so found a start in the movie business. It was a tight little group. Everybody knew everybody. In March 1963, when he married his second wife, Judy, a model, the entire film industry was at the wedding in the registry office and then everyone went to his house in Montpelier Street.

Impossible as it is to believe now, London was a cheap place to live. And making movies was easier.

“Here’s the thing,” says Gene. “Back then you were the producer. One producer. Now you watch the print of Repulsion, Cul de Sac or the Vampire Killers and there’s one producer. Gene Gutowski. Now you see a picture. The producer credits go on and on. The agent wants a producer credit. The guy who makes sandwiches wants a credit too. In those days there was one producer. That’s it. It was a lovely cozy business then in England. All the major Hollywood studios had their offices in London , and these guys were easily accessible.”

You had more responsibility, but more control. You got the rewards and the blame.

“Exactly,” says Gene. “But making pictures was much, much cheaper, too.”

In today’s climate a film like Repulsion (1965) probably wouldn’t get made. Were you aware how special this film was while you were making it?

Gene is laughing now.

“No. Oh, my god, no! We were just making a picture. We thought it was great but when it came out and Bosley Crowther, who was a big critic at the New York Times, said he thought it was something everyone should see, we knew we were home free.”

I wonder if he has been running from or toward something all his life. We all might ask ourselves the same question.

“Just running,” says Gene.

Just running.

Through the war. Through the American intelligence service. Through New York in the 1950s. Through London in the sixties. Through films that worked and films that didn’t Through businesses of many stripes. Sic transit Gloria mundi . . . Through four marriages out of which he salvaged his most prized achievement, his three sons and their grandchildren.

Family remains constantly on his mind.

“I started life in total denial,” Gene says. “I invented a completely new identity. I beat up on myself. I never admitted I was Jewish. Not even to my own family. Not until a few years ago. It wasn’t about being Jewish. To start with I have absolutely no religious training. In our home they used to slaughter pigs for Easter and make sausages. Not very Jewish is it?”

We’re looking through old photographs again now.

There he is, smiling with his friends by a swimming pool, circa 1943, in the depths of war when in his spare time he’s stealing radios from the Germans. How is one able to do that?

“You don’t show fear,” he says slowly. “The trouble with the Jews was that even when they had the so-called “right look,” it was the fear in their eyes that gave them away. I never had fear in my eyes.”

And he still doesn’t, facing the short tomorrow, just that same sparkle that resonates from the old black and white photo.

What are the other things that are most important in life?

“Having enough money to enjoy yourself and friends who are loyal.”

What was the worst mistake he ever made?

“Turning down Stanley Kubrick and Mike Nichols. I was too ambitious. I’d been promised a three-picture deal. So I blew off Mike Nichols and Kubrick. Bye bye! Poor Mike Nichols even borrowed Burton’s apartment at the Dorchester to impress me, a schmuck from Lvov . It’s too painful to discuss. It’s definitely the biggest mistake I ever made business-wise.”

“You can’t really make a bigger business mistake than firing Kubrick and Nichols?” I say.

“It’s difficult to beat.”

His greatest experience?

“The Pianist was a good one. I suppose you could call that payback for all the denials.”

In your autobiography you wrote about trying to analyze the effect of the loss of your family on your pursuit of the good life over the perspective of time, about realizing loss and the pain that goes with it. I can only wonder what it must be like.

Gene pauses and says slowly, “I’m like so many people who came out of the Holocaust who are unable to deal with the tragedy and the losses. You want to go into complete denial put out of your mind what happened to you, invent a new curriculum vitae for yourself . . . put out of your mind what you’ve experienced, what you’ve seen. How else can you deal as a 15, 16 year-old boy when practically overnight the entire family is wiped out? Your grandparents, your cousins, your uncles, everybody. You’re alone. You’re a fucking orphan. The worst part of it is I had a young brother who was left behind in Lvov and who wrote me a desperate letter once to help him and I wasn’t able to. That’s excusable. How could I have helped him? Yet the sense of guilt has been with me throughout my life. I should’ve been my brother’s keeper. I couldn’t have been. You know? These are the issues and you submerge yourself in life, in women in sexuality. I’ve done it all. You name it . . . You live with a tremendous sense of loss, which as I get older is getting stronger and stronger, but I was fortunate that I was able to extend my life because I have three sons and they have children so I see the continuation of the family, which otherwise would’ve been wiped out. In the end life wins over death. Right? That’s the essence of it. You see this may sound vain and probably is because in a way I probably am a vain man but I am very proud of the genetic background. I have a very handsome family on both sides and I see the continuation of the good genes in my children and their children and that makes me very happy. They are good-looking intelligent, creative and successful in life at what they do. Life wins.

For example nothing pleased me more than a vast collection of beautiful London tailored suits that I was able to give to my son Andrew who is exactly the same size as I was way back when. With that gift he became the best dressed real estate developer and architect in America . My other son, Adam is a documentary film producer who has a film about Halston (the iconic seventies designer) in the Tribeca Film Festival this month. My other son has been a yacht captain based in Monte Carlo for years.”

Gene smiles.

Bon mots from a bon vivant.

“In this way even elegance carries on. I’ve assured myself of the continuation of life afterwards.”